INTERNET

COMMUNITY EDUCATION

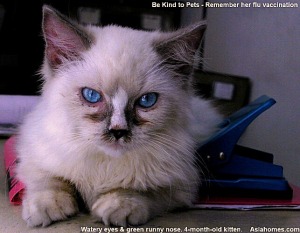

"Be

Kind to Pets" - Tips for a longer life for pets. A Community

Education supported by Asiahomes Internet.

Article written in June 21, 2002.

The 24-hour guarantee expired

for the sneezing Ragdoll.

The four-month-old kitten was sold with a 24-hour return guarantee that

the money would be refunded if the cattery's veterinarian certified that it was suffering

from a bacterial or viral infection within 24 hours of purchase. It was sold with

the information that the kitten had been on two types of medication - one being an

antibiotic and one to stop runny nose for the last eight days.

Now it was four days after purchase and the guarantee would not apply. The right

lower eyelid of this Ragdoll was redder than the left eye as it had conjunctivitis.

A thick and moist greenish black crescent of tears stained the side of nose on each side

below the eye. Now it was four days after purchase and the guarantee would not apply. The right

lower eyelid of this Ragdoll was redder than the left eye as it had conjunctivitis.

A thick and moist greenish black crescent of tears stained the side of nose on each side

below the eye.

"The kitten has a dark green discharge from its nose and is sneezing. It was not so

active the last two days. What's the problem?" the Owners asked me. I could see the

mucus oozing from the small nostrils and hear the faint sneezing. The

Ragdoll was

not well but it was not terribly sick at the time of examination.

"The Ragdoll has an upper respiratory tract infection," I said. "There is a

bacterial and possibly a viral infection of the nose and throat. The kitten objected to

any thermometer being placed into its rectum to check whether it had a fever or not. It

was still strong to resist such nonsense from the veterinarian. I looked at the tongue. It

was redder than normal and this could be a sign of fever.

I auscultated the chest of this quiet blue-eyed kitten with my stethoscope. "The

lungs are normal presently, but the infection may go further into the lungs causing

pneumonia and death. Much depends on the kitten's immunity to infections."

What was the cause of this

upper respiratory tract infection? Singapore catteries sell kittens brought in

from various sources - local and imported ones. It would be difficult to prevent viral

infections. Feline herpes virus 1 and caliciviruses are the most

common ones causing runny noses and sneezing.

"Was the kitten vaccinated twice?" I asked the Owners. Usually the pet dealer

would provide a vaccination certificate during sale but there was none in this case. The

cat dealer was contacted by mobile phone but there was a voice mail.

Now, what should I do? An antibiotic injection was necessary. More oral medication

for the next few days? It would not be easy for many new kitten owners in

Singapore to medicate a kitten.

Ideally, the

kitten should be warded and given injections for the next three days but would the Owners

bear the separation? What if the viral infection, for which there was no effective

drug cause the kitten's health to deteriorate and kill the kitten? The veterinarian

would be blamed.

Signs of upper respiratory tract infection may recur although the

kitten may be vaccinated. It may be vaccinated when it had maternal

antibodies and therefore, the vaccination would not be effective.

At week 6, the first vaccination is usually given in reputable

catteries in Singapore. and most kittens would not have

maternal antibodies to make vaccination ineffective.

|

|

|

Blocked nose with greenish

discharge and tear stains from sore eyes in a sick Ragdoll kitten when first seen by the

veterinarian.

|

Usually the viral cause is the rhinotracheitis and the

calicivirus infections complicated by bacterial infections

like chalmydosis. |

Ragdoll recovered after 7 days and went home to a happy

owner. |

| |

|

|

| |

Clear eyes and nose in another healthy Ragdoll |

Clear eyes and nose in another healthy Ragdoll |

VIRAL INFECTIONS OF CATS IN

SINGAPORE

The commonest complaint of viral infection is the runny eyes,

coughing and sneezing in kittens and cats. This upper

respiratory tract infection is usually not fatal and is caused by

the rhinotracheitis virus (also known as the feline herpes

virus 1). A vaccinated cat may not show signs of runny eyes

and sneezing. Calicivirus also cause upper respiratory

tract infection.

Panleukopenia, or feline distemper are viral infections which

can kill cats. Vaccination works well as there are few cases seen in

practice.

Feline corona virus is a common intestinal virus that may

cause no

clinical signs or may cause diarrhea in cats who are infected with

it. This is

considered to be a minor viral infection in most cases, but when

feline

corona virus mutates, it can become deadly. If the mutant virus can

invade the rest of the cat's body it is referred to as feline

infectious

peritonitis (FIP), which is almost always a fatal infection.

There is a

vaccination for this virus but there are some questions about how

well

it works and most veterinarians do not use the vaccine on a routine

basis.

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV)

and feline leukemia virus (FeLV) are

retroviruses. These are viruses that attack the immune system and

weaken

it. This can lead to severe infections or even cancer in cats

infected

with these viruses. There is no vaccine for FIV at this time. There

is a

vaccine for FeLV. It is not as effective as vaccines against other

types of

viruses are but it works well enough that most veterinarians

recommend it for

cats who may be exposed to an infected cat. This would include

outdoor cats,

cats who live indoors and outdoors and even indoor cats who are

routinely exposed to a cat who goes in and out. Cats are most

susceptible to

feline leukemia virus when they are young and develop a natural

immunity as

they get older.

Feline leukemia virus was discovered

in 1964 and a test to detect it

that could be used in veterinarian's offices was developed in 1973.

A vaccine

was not approved until 1985, so it took almost twenty years for a

vaccine to reach the market that would help prevent this disease.

Over the last five or six years it

has become apparent that some cats

vaccinated against feline leukemia virus developed cancers where the

vaccines were given. The cancer is usually fatal if untreated

somewhere

between 50 and 70% of cats in which the cancer is treated will die

from

it. The rate of development of this cancer is thought to be between

1 in

2500 and 1 in 10,000 cats who are vaccinated against FeLV. Due to

this

problem, veterinarians are trying much harder to figure out if a cat

is at risk

for getting feline leukemia virus before giving the vaccine. In

young cats,

it is usually better to give the vaccine if there is any suspected

risk. In

older cats (over 2 years of age) it is probably better not to give

the

vaccine unless there is a definite risk of exposure to an infected

cat.

|

INTERNET

ADS

INTERNET

ADS